Box Counting Arithmetic

I was recently invited to a wedding of a friend, where I had the pleasure to meet the the 4-year old Benjamin1 who was fascinated by numbers and arithmetic. Sharing and often repeating the laments of Paul Lockhardt, I was eager to show him some aspects of mathematics, that are fun to explore and not commonly taught in schools.

Given his young age and tiny size he had already mastered a fair amount of arithmetic. His favorite topic where gigantic numbers. He had a 30page(!) list of large numbers with their names (Billion, Trillion, etc.) with him and he had a burning question for me at the very beginning:

“What is the largest number that has a name?”

The largest number in his book was the GoogolPlex ($10^{Googol}$), but he suspected that there are even larger numbers which have a name. While that question is a little deeper than I was comfortable going into at that point (cf. Interesting Number Paradox), we settled for the moment, by creating another number which was even larger than the GoogolPlex:

I suggested to name the number Rachel1 in honor of his mother, but Benjamin replied: “This is not a good name for a number”. So we went with “GoogolPlexilliardenSeptillion” and appended it to his list.

While gigantically large numbers fascinated him clearly most, he also had a considerable fun at solving arithmetic puzzles (), and so I told him the following box counting game.

Numbers and Boxes

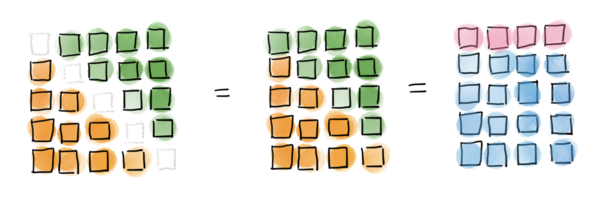

Many arithmetic questions can be conveniently translated into geometry using the following rules:

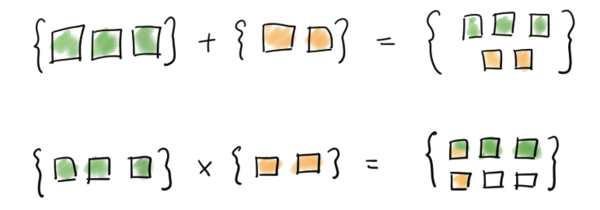

- We represent number $n$ as set of $n$ boxes. The size and color of boxes do not matter.

- Box sets can be added by merging them.

- Box sets can be multiplied by counting boxes in rectangles.

Now what can we do with this almost trivial translation of numbers into boxes?

The main observation is, that now

Every multiplication becomes a problem of counting boxes in a rectangle!

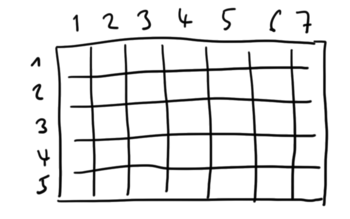

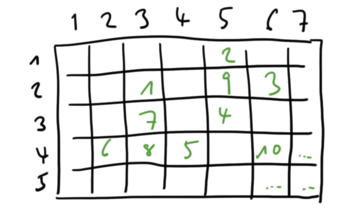

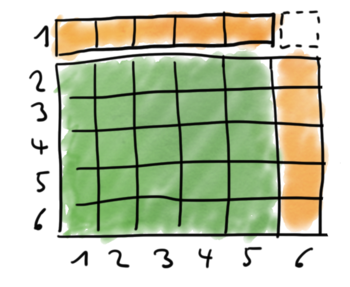

Warmup: What is 7x5?

Presented as a box counting problem, we ask how many boxes there are in a 5x7 rectangle!

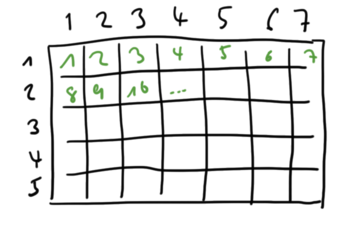

There are many ways to count the boxes, e.g. by crossing one off after another:

But we might also apply some systematic, like this one:

or this one:

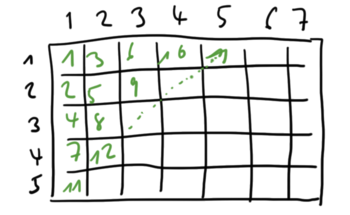

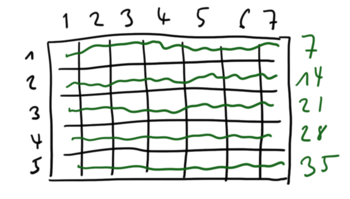

Most people would approaching this problem by reciting the succession of multiples of seven: 7,14,21,28,35. In terms of box counting this corresponds to this pattern here:

In fact, this is more a decomposition of the rectangle in multiple lines, as a simple counting pattern. And it reveals a very powerful technique for counting box arrangements:

Divide and Conquer: Chop the rectangle into smaller rectangles, that are easier to count.

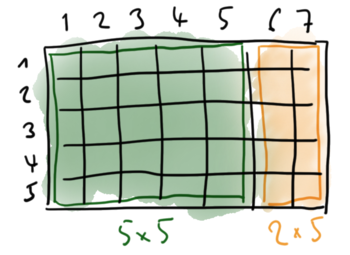

If you approach $7\times 5$ as a decomposition problem, the following decomposition seems more natural and yields a quite convenient way to calculate $7\times 5$ as:

Here is another variant: If you rearrange the 5x7-rectangle as follows you get the identity

That was neat, wasn’t it?

What is 11x11?

Let’s do another example: What is 11x11.

I asked Benjamin to calculate this number, and he proceeded, as expected, by the standard method of reciting the 11 succession. It was quite impressive to see him handling these calculations at pre-school age and arrive at the correct answer: 121.

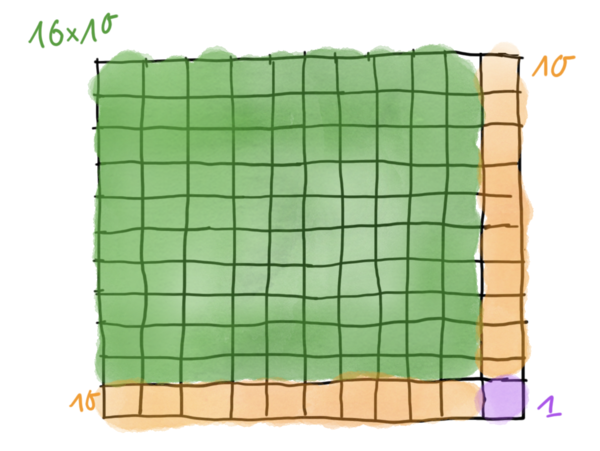

However, I had just asked him, 10x10, which he knew by heart: 100!

So essentially, he had just counted all boxes in a 10x10 square. And posed with the problem of counting all boxes in an 11x11 square, which is just 1 box larger, he started from scratch and recited his series. Poor boy!

Here is how you do better:

A Square Number Theorem

Those simple observations already open up more questions about the large and fascinating topic of square numbers.

The above trick to calculate 11x11 generalizes to the following theorem.

Theorem. The number of boxes in a square of size $N+1$ is equal to the number of boxes in a square of size $N$, plus $2N$ (at the sides) plus 1 (at the tip).

It’s not possible to provide a formal proof using the explicit box counting methods introduced above. We either need more profound set theory and induction, or formal arithmetic $(N+1)^2 = N^2 +2N + 1$, which derives this in a breeze. However, there is value in illustrations. Benjamin followed that argument quickly, while working with parameters $N,x$ and the binomial theorem would have been too much and/or boring for him. And frankly, most schools don’t bother to present proofs at all and stay at the phenomenological level.

Ok, here is another exercise:

What is 13x13?

If you followed through to here, you will directly say:

But you might not remember what $12 \times 12$ is. Do you?

So, let’s calculate that first. So what is 12x12?

“I know!”, you will now say, “We can apply that same trick again!”. And indeed:

Fortunately we have already calculated $11\times 11 = 100 + 21$ so that we can substitute.

Which I’ll leave for you as an exercise from here.

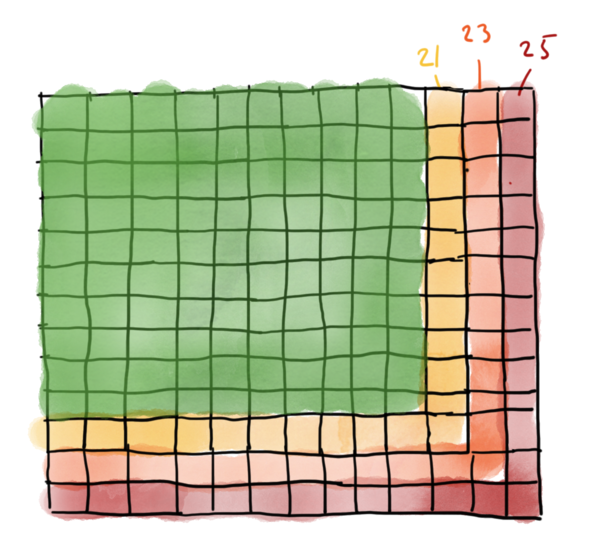

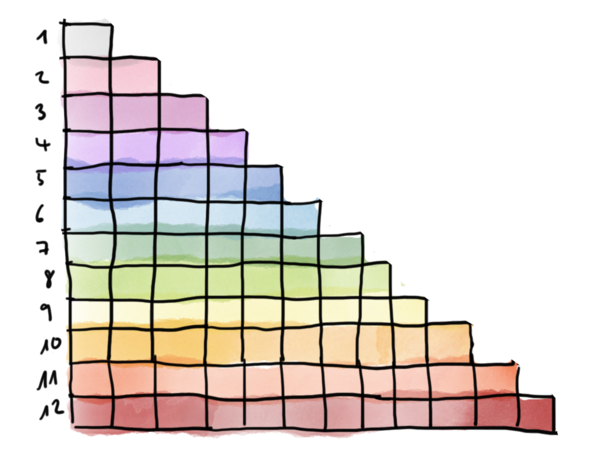

From the perspective of counting boxes, we have just performed the following construction:

Ha, that’s interesting. We decompose a square into layers of square-angles!

But we don’t have to stop at 10x10. We can go all the way down to 1x1!

But wait, there is another pattern: The size of those square angles are just the odd numbers!

Theorem. The number of boxes in a square of size $N$ is equal to the sum of all odd numbers smaller than $2N$.

Sums of even numbers.

We have just discovered that the sum of odd numbers are squares. This raises the next interesting question immediately:

What are the sums of even numbers: $2 + 4 + … + 2n$ ?

There is a cheap trick, how you can get from all odd numbers to all even numbers: You can subtract one!

There is a special box, in each square-angle which seems predestinated for being tossed: The diagonal box:

Looking at this picture, we can see, that The sum of even numbers up to 24, is equal to the full square of size 13 minus the diagonal with 13 elements:

Generalizing, we find another pattern:

Theorem. The number sum of all even numbers smaller or equal to than $2n$ is $(n+1)^2 - (n+1)$

We are not at the end. There is another trick that can be applied.

By removing the diagonal the box count just got symmetric! There are as many boxes on the top as there are on the left side: In other words we can extract a factor of $2$:

Combining both tricks, we have just found another derivation of the Little Gauss’ Theorem:

Theorem (Little Gauss). The sum of all number smaller or equal to $n$ is

Going further

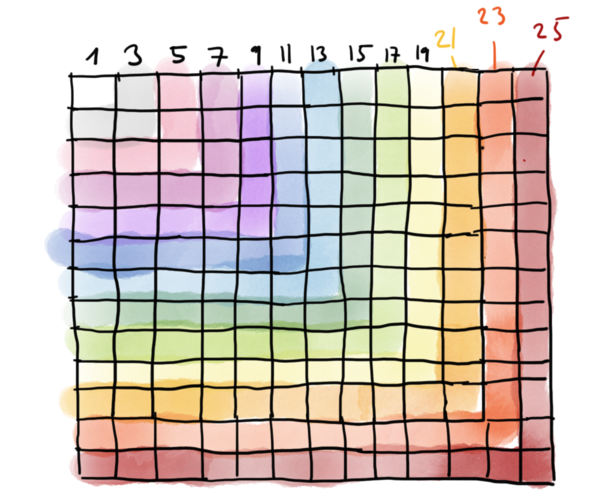

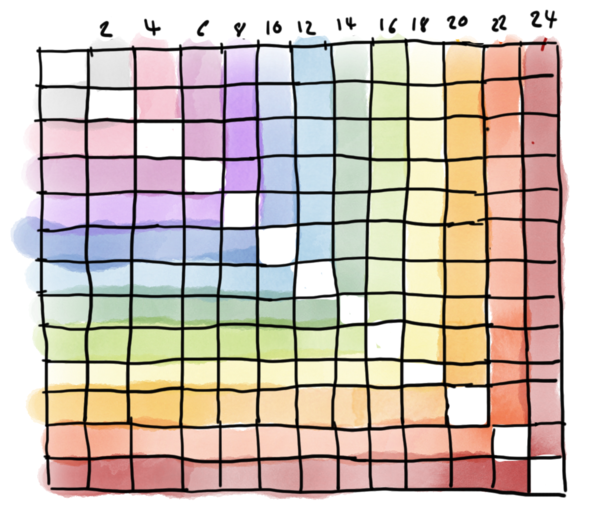

We are clearly just at the beginning here. Framing arithmetic problems as box counting problems allows creative approaches and raises many interesting questions: Can you find the identity hidden in the picture at the very top?

Meta

- The images have been created with a HUION Tablet (this is an Amazon-affiliate link) and Sketches by Tayasui.

- Thanks for your comments and corrections. I am fixing those as they appear. Check the Version History to see what changed and when.